Bangladesh has recently been upgraded from low-income country (LIC) to lower-middle-income country (LMIC) as per the World Bank’s classification. There is an aspiration for graduating from the LDC status to that of a middle-income country by 2021 as per the United Nations’ classification. In this context, it is very important to assess the capacity of the country’s social infrastructure in achieving the desired level of economic growth rate and subsequently, the targeted per capita income level.

As far as the social infrastructure, in terms of education and health, is concerned, there is a valid question to ask, whether Bangladesh is poised for leaping towards a middle-income country. In this paper, we focus on two indicators, public expenditure on education as % of GDP and public expenditure on health as % of GDP. It is well established in the economic literature that strong bases of education and health are needed for a country to accelerate and sustain economic growth.

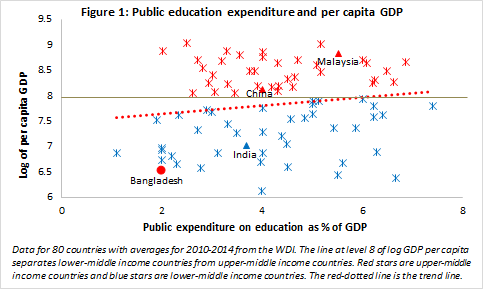

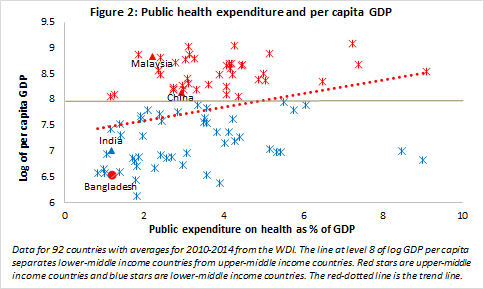

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, we have presented two scatter-plots involving public expenditure on education as % of GDP and public expenditure on health as % of GDP respectively against the log of GDP per capita for the lower-middle-income countries and upper-middle-income countries as per the World Bank’s classification. The data are the averages for the years between 2010 and 2014 and they are derived from World Bank’s WDI. In both scatter-plots, the horizontal line at the level of 8 of log GDP per capita separates lower-middle-income countries from upper-middle-income countries. Bangladesh’s position is shown by the red circle.

Even these simple scatter-plots present some very interesting insights. In Figure 1, the trend line suggests that the association between public expenditure on education as % of GDP and log of GDP per capita for 80 countries (involving both lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries) is positive. This evokes that countries with higher public expenditure on education as % of GDP tend to be associated with a higher GDP per capita. It is interesting to see that all upper-middle-income countries are well above the trend line; whereas, most of the lower-middle-income countries are well below the trend line while some of them are just on the trend line. Bangladesh’s position is among the worst-performing countries, as its public expenditure on education as % of GDP (around 2%) is much lower than those of all upper-middle-income countries, and is even much lower than most of the lower-middle-income countries. A similar pattern is observed, as depicted in Figure 2, in case of the association between public expenditure on health as % of GDP and the log of GDP per capita. Once again, Bangladesh appears to be among the worst-performing countries with only a 1.2% share of public expenditure on health in GDP. Interestingly, the positive association between health expenditure and GDP per capita (Figure 2) seems to be stronger than that of between education expenditure and GDP per capita (Figure 1), which is supported by empirical literature that health expenditure has a relatively more immediate positive effect than education expenditure on economic growth.

The aforementioned exercises suggest that Bangladesh has to improve social infrastructure significantly in her way towards a middle-income country. There are two critical lessons for Bangladesh. First, the current allocations for education and health expenditure as % of GDP need to be almost doubled from their current meagre levels (China and Malaysia, depicted in Figures 1 and 2, are good examples). Second, the efficiency of public expenditure on education and health in Bangladesh needs to be improved. There are some countries (both in categories of lower-middle income and upper-middle income) who have been able to achieve much higher levels of GDP per capita than that of Bangladesh even with similar proportions of education and health expenditures that Bangladesh has.

RECENT COMMENTS