In 1981 Bangladesh had 45 million people in the working age population in the range of 15-64. Male labour force participation was 84%. Female labour force participation was only 4.5%. Most of the workers were employed in the agricultural sector. This was the set-up when the Readymade Garment (RMG) industry started in Bangladesh. It is no miracle that women got more employment in the garment sector. The magic lies in wages. Unlike the Lewis Model that assumes surplus labour being absorbed in the capitalist sector, this labour actually comes from unused labour who were not in the labour market at all. The higher the number of labours unused in the economy, the greater the potential for developing a labour concentrating industrial sector like textile and RMG.

The same path has been seen in other industrialised countries: England during the early nineteenth century, New York in the early twentieth century, Hong Kong, South Korea, Vietnam and China in the mid to late twentieth century. Textiles and RMG worked as stepping stones everywhere before moving to other sectors in a higher global value chain. In all the mentioned countries, during the take-off years to industrialisation, they planned for industrial diversification and invested more in education and healthcare. In other words, investment was not only in physical infrastructure and physical capital but also in human capital. This is where Bangladesh diverged from others.

When the RMG investment started in the country, Bangladesh had no other major manufacturing exports. RMGs were given many benefits to foster quick growth, such as duty-free imports, bonded warehouses, and direct cash benefits. It boosted the sectorial growth but at the cost of lower incentives for less diversification. It created a shadow incentive for producers to concentrate solely on the RMG investment.

The new class of capitalists in Bangladesh were mainly the RMG investors. They were also heavily linked to the political parties. Since the 1990s, at least a quarter of the members of parliament were directly associated with RMG industries. The interests of the policymakers and capitalists were so hand in hand that they had the same aim of keeping the wages low so that the cost of labour remained cheap. Also, given that the scope of corruption was higher in infrastructure, the government was more interested in spending after infrastructure than investing in human capital. (This is why all the prominent party leaders in the past incumbent governments were prized with ministries such as the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) or the Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges – two ministries associated with most of Bangladesh’s infrastructure projects.)

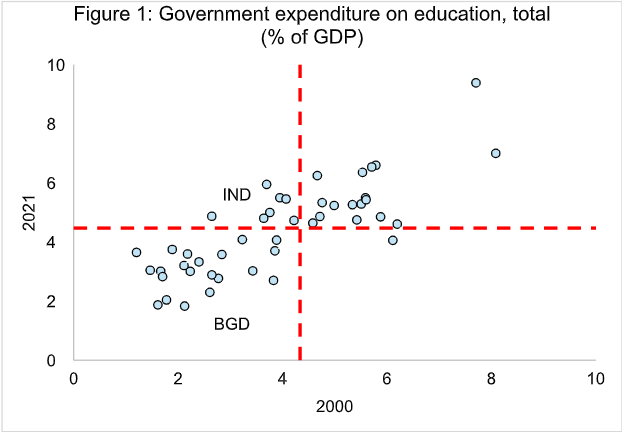

In early 2000, Bangladesh spent 2.1% of its GDP (20% of the total budget) on education. In 2023, the share fell to 1.78% of GDP (and 10.7% of the total budget), one of the world’s lowest (Figure 1). One reason our education expenditure has remained relatively stagnant is due to capitalist incentives. Higher education is not required for labour-intensive capitalist sectors like the RMG. Education is often attributed to more awareness, and educated workers are more difficult to oppress. Given that until recently, the technology in the RMG was mostly labour-driven, there was no incentive from the capitalist-aligned policymakers to improve the quality of education. Over the years, Bangladesh’s RMG wage growth was much slower than the total RMG production growth. This shows that the capitalists had more profits in their bags than they spent after workers’ wages.

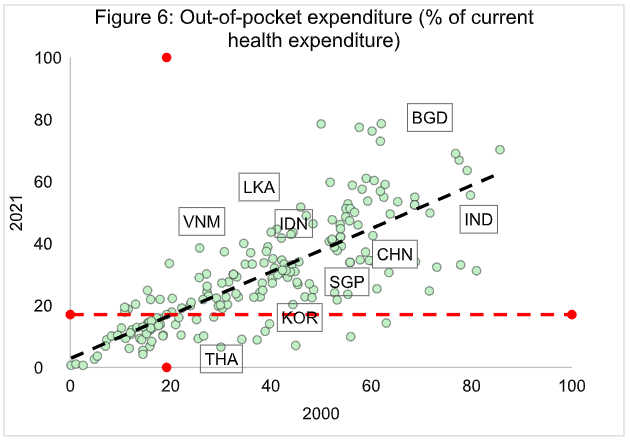

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data; Note: The vertical red dotted line corresponds to the 2000 world average, and the horizontal red dotted line corresponds to the 2021 world averages.

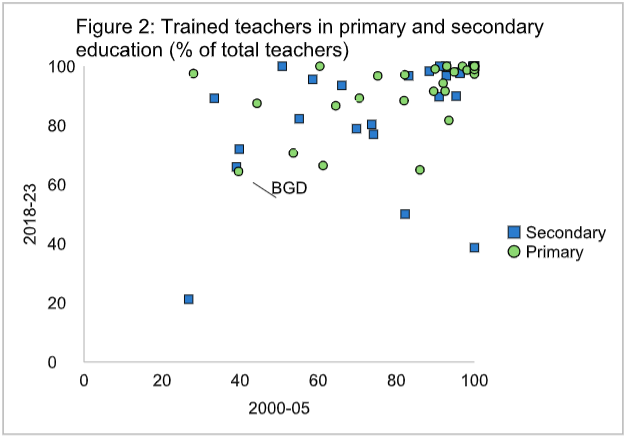

Therefore, it is no surprise that Bangladesh spent more on infrastructure during this period than on education or training. Lower spending on education has led to inadequate numbers of teachers and schools, keeping the pupil-teacher ratio higher than the global average. More so, the proportion of trained teachers in primary and lower secondary education in Bangladesh is among the lowest in the world (Figure 2).

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data;

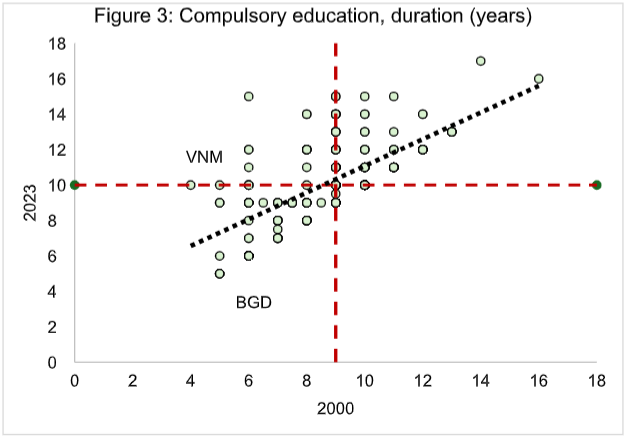

Also, from the policy point of view, Bangladesh has not driven any major education policy reviews in the past few decades. For example, in early 1990, the mandatory education level for Bangladesh was year 5. Our comparator Vietnam had the same, but they increased the mandatory education level to Year 10 in the early 2000s. Currently, Bangladesh is among the countries with the lowest mandatory education levels in the world (Figure 3). All these lead to lower education performance of pupils at school, higher secondary school dropout rates, and higher youth NEET (not in education, employment or training) rates. Unsurprisingly, Bangladesh tops all these rankings in the world.

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data; Note: The vertical red dotted line corresponds to the 2000 world average, and the horizontal red dotted line corresponds to the 2023 world averages.

The increased crimes and moral destitution that we see in Bangladesh now can be largely attributed to these social failures. Quality education is the only thing a country and a civilisation need to succeed and prosper. Historically, all great civilisations of the past, be it Plato’s Athens, Aurelius’s Rome, Rashid’s Baghdad, or in modern times, countries like Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong or Vietnam – had emphasised one thing: education.

One great example is Vietnam: Vietnam introduced their Doi Moi reformation in the late 1980s. They increased their spending on education, reformed their curriculum, and trained their teachers. According to the PISA test results, their education is considered one of the best performing in the world.

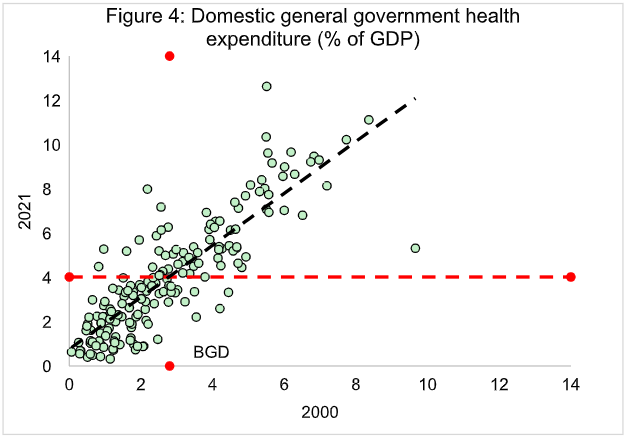

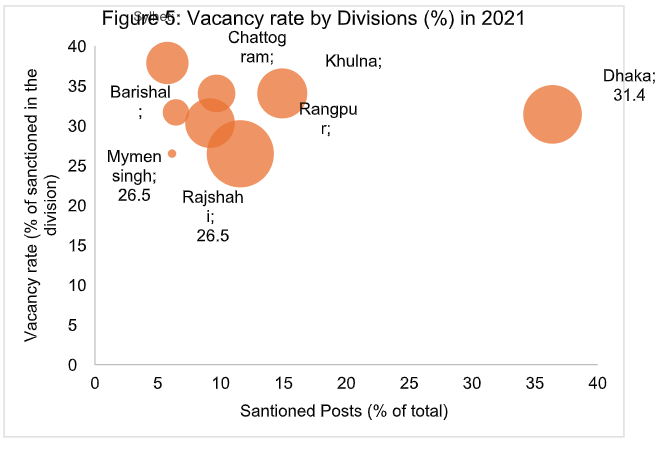

A similar grim picture is observed in the case of healthcare. Regarding government expenditure on healthcare (as % of the GDP), we were one of the countries with the lowest spending in the 1990s, and we still are (Figure 4). Countries like India or Thailand increased their spending by at least threefold between these periods. Also, Bangladesh spends more on equipment or infrastructure than hiring trained doctors and nurses. In 2021, almost one-quarter of the healthcare staff positions under the DGHS were vacant (Figure 5). One of the reasons behind this was lengthy and faulty recruitment practices. This process is often further plagued with corruption at different stages of the recruitment process (eg, bribes during police verification, political alignments during transfers, etc.).

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data; Note: The vertical red dotted line corresponds to the 2000 world average, and the horizontal red dotted line corresponds to the 2021 world averages.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Health Labour Market Analysis in Bangladesh (2020-21)

The mess in the healthcare sector is primarily a policy failure. Bangladesh has no strict regulations on who can open a diagnostic centre. Hundreds of diagnostic centres across the country do not have any certification or adequately trained staff. The lack of laws and orders creates the perfect ground for moral hazards in the healthcare sector. Without proper regulation and monitoring, the best way to earn profits is to charge higher while giving the least service.

This could explain why so many Bangladeshis prefer to have their treatment in India, where the treatment is reportedly cheaper than in Bangladesh. Another reason our healthcare system did not improve over the years is that all our policymakers go to Singapore or Thailand rather than Dhaka Medical College for their treatment. When the public policymakers do not go to the public hospitals, the sectors are likely to fall.

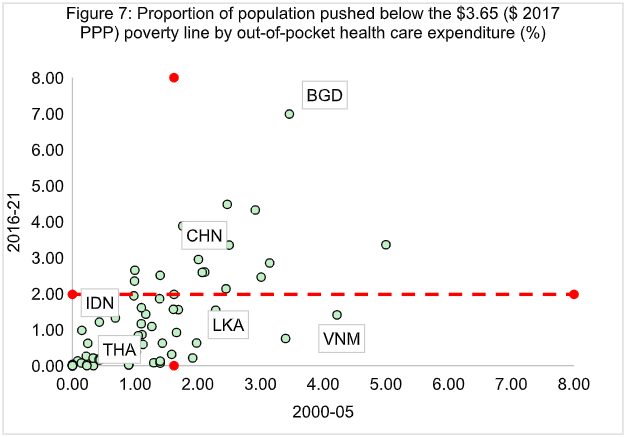

Due to the low public expenditure and sub-standard healthcare services without minimum monitoring, the out-of pocket healthcare expenditure in Bangladesh is one of the highest in the world (Figure 6). Such higher healthcare expenditure has severe distributive economic consequences. As the World Bank modelling shows, in Bangladesh, out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure pushes nearly 7 percent of our population below the $3.65 poverty line. Again, Bangladesh is an outlier among all the countries on this parameter (Figure 7).

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data; Note: The vertical red dotted line corresponds to the 2000 world average, and the horizontal red dotted line corresponds to the 2021 world averages.

Source: Author’s calculations based on WDI data; Note: due to data limitations, we considered the periodical average for the mentioned years. The red dotted line corresponds to the world average for the respective periods.

Society is like a neural network in our brains. Every part of the society is interlinked. Damage in one part can lead to damage to the whole. Likewise, only developing a part of the network will not lead to the development of the rest of the system. The social objective function is Rawlsian in nature: our outcome is defined by the minimum. This is the reason why Bangladesh is in a mess right now. We had infrastructure developments where corruption was easy to commit. We did not have development in health and education because our political leaders or policymakers did not have any incentives to do so.

What Bangladesh needs right now is a strong policy on education and healthcare. Of course, higher spending on education and healthcare will not ensure the solution to everything. A solid policy framework must drive higher spending like Clement Attlee did in the 1950s in the UK to reform the education and healthcare sector and Mahathir Mohammad in the late 1970s to reform Malaysia.

To address these critical challenges, Bangladesh must prioritise a significant shift towards human capital development. This requires a substantial increase in public spending on education and healthcare, aiming to allocate at least 6% of GDP to education and 5% to healthcare, in line with international best practices. Concurrently, a comprehensive reform of the education system is imperative, including extending mandatory education to at least ten years, significantly improving teacher training and salaries, and modernising the curriculum to international standards. Strengthening the healthcare system necessitates increased public sector investment, improved medical staff recruitment and training, and robust regulation of the private healthcare sector. Finally, combating corruption at all levels is crucial to ensure the effective and equitable allocation of resources in both sectors.

We need to learn from our mistakes before it is too late. The more we delay, the more prolonged our crisis recovery period will be.

This article was first published in the January, 2025 edition of the Thinking Aloud

RECENT COMMENTS