To guide youth development efforts, the National Youth Policy 2017 was developed, which defines youth as individuals aged 18–35. In contrast, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) defines youth as those aged 15–29. Considering both definitions, more than 35% of the country’s population falls within the 15–34 age group, underscoring the significant demographic window of opportunity Bangladesh is currently experiencing. While opportunities abound, the question remains: how well-equipped and prepared are the youth to transform this demographic advantage into tangible dividends?

To explore this issue, the South Asian Network on Economic Modelling (SANEM) and ActionAid jointly conducted a nationwide survey titled “Youth in Transition: Navigating Jobs, Education, and the Challenging Political Scenario Post-July Movement” between May 20 and May 31, 2025. It covered 2,000 individuals aged 15–35 from all eight divisions of Bangladesh, encompassing both rural and urban areas and diverse backgrounds.

Among the respondents, 44.48% were students, with a majority aspiring to government jobs (55.67%), followed by entrepreneurship (15.60%), employment abroad (9.65%), and private-sector jobs (6.96%). Female youth showed an even stronger preference for government jobs (66.33%), followed by careers in academia (7.40%). However, 73.14% of students rated their preparedness as average to very poor, indicating a lack of confidence in pursuing their desired careers. Additionally, 44.29% feel their education is not adequately preparing them for the job market, while only 38.50% and 21.21% believe their education is preparing them moderately and significantly, respectively.

The job market is evolving rapidly due to technological advancements and shifting global dynamics. However, both the labor market structure and the education system in Bangladesh are struggling to keep up. For instance, according to BBS, two million youths are unemployed, and the youth unemployment rate is three times higher than the national average. Furthermore, eight million youths are classified as NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training).

Despite most unemployed youth seeking jobs through the internet, newspapers, and personal networks, the survey found that 74.18% had not applied for any jobs in the past twelve months—a figure even higher among female respondents (80.47%). This may be due to either a lack of job opportunities or a mismatch in skills and qualifications, with the latter being more probable, as 82.55% did not attend any vocational training in the past year. Among those who applied for at least one job, 45.12% were not invited to any interviews, despite 85.14% having attained higher secondary to tertiary-level education. This points to a serious mismatch between educational qualifications and labor market requirements.

Employed youth, on the other hand, are predominantly engaged in low-paying jobs. Among full-time workers, 33.73% earned up to BDT 10,000 per month, while 43.49% earned between BDT 10,001–20,200, and only 20.72% earned between BDT 20,001–50,000. For part-time workers, 72.65% had a monthly income of BDT 10,000 or less.

The survey also identified a group of youth who had neither sought paid employment nor attempted to start a business in the past month, probing the reasons behind their economic inactivity. A total of 782 youth (39%) fell into this category, of whom 462 were students. The remaining 320 had either completed or discontinued their education or had never attended school. While economic inactivity among students is understandable, the same cannot be said for non-students—especially since 94.69% of this group were female. When asked about their reasons, 78.61% cited household responsibilities, followed by 9.64% who expressed no desire to work.

Additionally, among youth who had discontinued education, males mainly did so to support their families (50%), followed by an inability to afford education (22.07%) and lack of interest (18.62%). In contrast, the primary reason for females discontinuing their education was child marriage (53.97%), followed by financial constraints (26.19%). Although 57.56% of this group were employed, 10.28% were still unemployed and 32.26% (244 individuals) were not part of the labor force. Thus, among the 320 non-students classified as economically inactive, 76.25% had discontinued their education. Given that 94.69% of them were female, this suggests that child marriage is a significant underlying factor preventing female youth from entering the labor force.

Furthermore, 40.07% of surveyed youth expressed interest in working abroad, primarily citing better salaries and benefits, a higher standard of living, and a lack of suitable domestic employment opportunities. Freelancing and gig-based work are also becoming increasingly popular due to the scarcity of traditional jobs, offering more flexibility and potentially higher earnings.

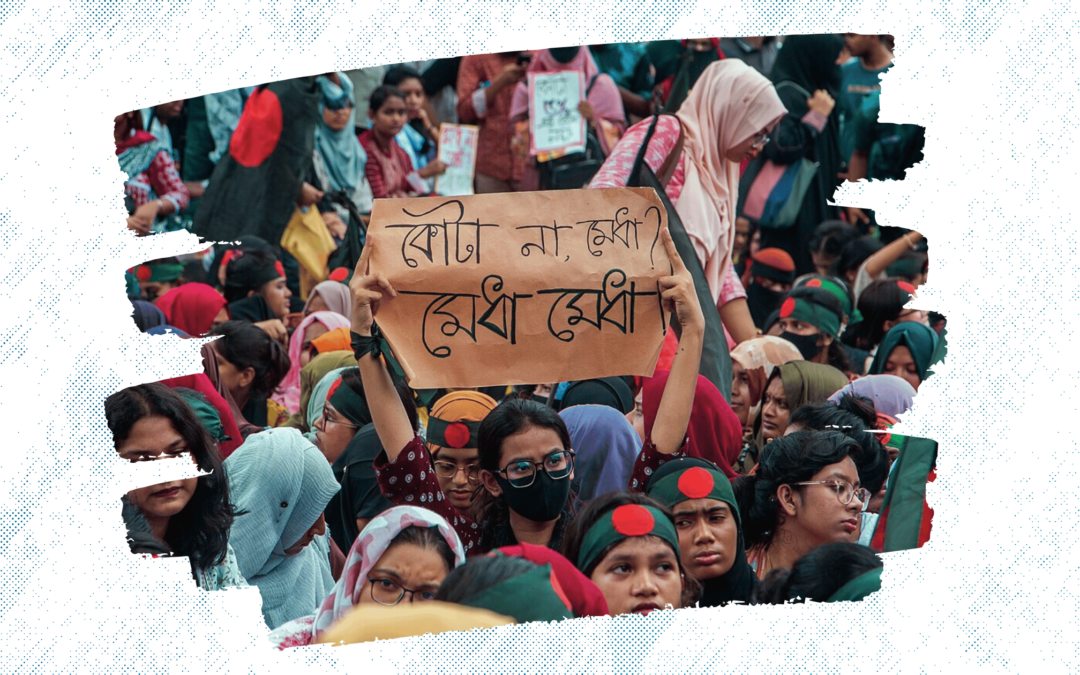

Despite these alternative avenues, structural barriers in the job market persist. The survey found that 54.72% of respondents identified corruption and nepotism as the primary obstacles to employment, followed by a lack of job openings, political bias, inadequate work experience, and insufficient skills. These findings paint a complex picture of a young population striving to adapt, innovate, and survive in a labor market marked by institutional inefficiencies, skill mismatches, and unmet expectations from the education system.

Addressing these challenges requires aligning education with labor market demands by integrating digital and soft skills, expanding vocational training, and strengthening industry-academia collaboration. To boost female participation, flexible learning, childcare support, and awareness against early marriage are essential. Promoting youth entrepreneurship through access to finance, training, and innovation hubs can create new pathways to employment. Ensuring fair recruitment by curbing corruption and expanding digital job platforms is also critical. Finally, youth engagement in policymaking must be institutionalized to make programs more responsive and inclusive.

RECENT COMMENTS