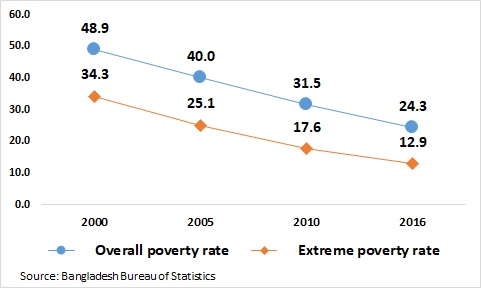

Bangladesh has made important progress in reducing poverty over the past one and half decades. According to the national estimates, the overall head-count poverty fell from as high as 48.9% in 2000 to 24.3% in 2016. Also, extreme poverty fell from 34.3% to 12.9% during the same period.

Despite its progress in reducing poverty, there are some major concerns regarding whether Bangladesh will be able to achieve the targets set by Goal 1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 with the business-as-usual scenarios. Goal 1 of SDGs sets the targets of eradicating extreme poverty and reducing at least by half the proportion of people living in poverty according to national definitions.

First, Bangladesh still remains a country with a very high incidence of poverty. In 2016, there were about 40 million poor people as per the national poverty line income. The number of extreme poor is also staggering with about 21 million people living below the extreme poverty line in 2016. If we consider World Bank’s Lower Middle Income Class Poverty Line, which has a value of US$3.2 (PPP, in 2010), in 2010, 59.2% people in Bangladesh were under the poverty line income in contrast to 31.5% poor people as per the national poverty line income. This suggests that small adjustments in the poverty line income can change the poverty statistics quite significantly.

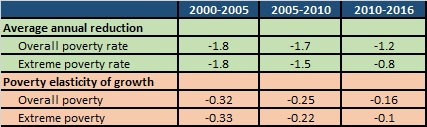

Second, the annual average reduction in poverty rates has declined gradually over the past one and half decades. During 2000-2005, the annual reduction in the overall poverty rate was 1.8 percentage points, which declined to 1.7 percentage points during 2005-2010, and further declined to 1.2 percentage points during 2010-2016. The most alarming trend is that while during 2000-2005, the annual reduction in the extreme poverty rate was 1.8 percentage points, the rate declined to 1.5 percentage points during 2005-2010 and to 0.8 percentage points during 2010-2016. This suggests that the scope and success in reducing overall and extreme poverty rates in Bangladesh have become limited in recent years.

Third, the poverty elasticity of economic growth declined over the past one and half decades, indicating a declining effectiveness of economic growth in reducing poverty. The poverty elasticity of economic growth shows the percentage point change in poverty rate due to a percent change in real GDP (gross domestic product). In case of overall poverty, such elasticity declined from 0.32 in 2000-2005 to 0.16 in 2010-2016. For extreme poverty, the elasticity had a larger fall as it declined from 0.33 to 0.1 during the same period.

Fourth, despite that during 2010-2016, the country witnessed the highest average annual growth rate in GDP, both the annual reduction in poverty rates and poverty elasticity of economic growth had the lowest values. This suggests that economic growth alone cannot take care of reduction in poverty. As per the calculated elasticity values of 2010-2016, and with the business-as-usual growth rate of GDP, Bangladesh will have an overall and extreme poverty rate of around 10% and 4% respectively by 2030. Even with an accelerated average growth rate of GDP of 8%, overall and extreme poverty rates, by 2030, will be around 6.5% and 2% respectively. This means that, though there will be some progress in reducing overall poverty, neither the business-as-usual nor the accelerated growth scenarios will be able to eliminate extreme poverty by 2030. Under the business-as-usual growth scenario, there will still be around 8 million extreme poor, and under the accelerated growth scenario, there will still be around 4 million extreme poor by 2030.

Despite accelerated economic growth in recent years, why has there been much slower progress in poverty reduction? Three critical factors can be attributed to this. First, the annual average number of generation of employment declined from 1.7 million in 2000-2005 to 1.3 million in 2005-2010 and further to 0.9 million in 2010-2016. This means the accelerated economic growth during 2010-2016 was not ‘employment-friendly’. Second, the annual average share of public expenditure on education in GDP remained frustratingly unchanged at around 2% throughout 2000-2016. Bangladesh is among the bottom list of countries in the world with the lowest ratio of public expenditure on education to the GDP. In contrast, such ratio is around 5% for most of the Southeast Asian countries. Third, the annual average share of public expenditure on health in GDP declined from around 1% in 2000-2005 to 0.9% in 2010-2016. The public health expenditure as the percentage of GDP in Bangladesh is one of the lowest in the world, whereas, such ratio is around 2.5% for most of the Southeast Asian countries. All these three factors contributed to a rising inequality too in Bangladesh over this period. While in 2000, the ‘gini’ coefficient, a measure of income inequality, was around 0.45, it increased to as high as 0.48 by 2016. There is now strong global evidence that the effectiveness of economic growth in lowering poverty falls with the rise in income inequality.

What needs to be done? In order to increase the effectiveness of economic growth in reducing poverty, the ‘jobless’ growth phenomenon needs to be avoided. For this, the economic growth momentum needs to be tuned for ‘meaningful’ structural transformations of the economy where the promotion of labor-intensive and high-productivity sectors would be fundamental. Also, poverty reduction is not simply about raising household income, but also about expanding human capabilities. In this context, Bangladesh has to increase the shares of public expenditure on health and education in GDP quite substantially in the coming years.

RECENT COMMENTS